SO MAYER: Being perceived, being heard: we often think about the painful aspect of that as being misheard, being criticised, being deliberately misunderstood, being shouted down. And I've experienced all those things, of course I have. But the possibility of actually being heard is equally as painful. Because it also asks what would be the result of that, that if someone said, "Okay. I've taken on what your book is saying. What now? Back to you." And that's what a good therapist does: "I've heard you. Now what are you gonna do about it?" And then going: oh, supposedly through my educational privilege, I've been taught to take power from using language. And here I am using language and I don't feel powerful. I feel afraid and I feel ashamed, and I feel like someone's gonna hit me in the mouth.

Read moreAllusionist 216. Four Letter Words: Terisk

Listen to this episode and find out more about the topics therein at theallusionist.org/terisk

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, hit language’s snooze button and language screams back, “I will not be snoozed!”

It’s the season finale of Four Letter Word Season, and I’m sad not to have covered every four-letter word in existence, but I’ve had a great time, beginning with the F-swear and going via dinosaurs, poisonous plants, the bain marie, a quiz, the scandal suffix -gate, to several local parks; and this episode returns to one of the strongest of the four-letter words we have covered, because there is still more to say about it.

Content note: this episode contains many category A swears, and some category B swears - it’s all educational though, not gratuitous or angry swearing, I promise. And sometimes I hear from listeners asking about the swear categories; you can hear all about them back in the early episode Detonating the C-Bomb, which also contains information that is related to this episode.

I’ll be performing at Nerd Nite at the Fox Cabaret in Vancouver on 10 September; I’ve linked to tickets at theallusionist.org/events and it’s a new piece about some mysterious Scandinavian translations of Dracula. I’ve been to Nerd Nite before and it was a very good evening of infotainment, I recommend.

Now, as I said, brace yourself for swears.

On with the show.

HZ: In the Allusioverse Discord community, we sometimes watch films and TV together, and a little while ago we were watching Legally Blonde, the tale of rich young white woman Elle Woods overcoming the adversity of being too femme-presenting for people to believe she could possibly study law.

And as we were watching Legally Blonde, we noticed something happening repeatedly in the subtitles. Three letters kept being asterisked out. Lines like:

“Actually, I wasn’t aware we had an ***ignment”

“You will get to ***ist on actual cases”

Again and again and again!

“This is Emmett Richmond, another ***ociate”

“We already ***igned the outlines”

“Equitable division of ***ets”

Did you deduce the missing word here?

The words spoken aloud were not bleeped out or blanked out or censored at all, so measures had been taken just to protect people who read the subtitles from the word ‘ass’. Which is not good subtitling practice. For added perplexingness, while the Legally Blonde subtitles had censored words like ‘associate’ and ‘asset’, words left intact included some slurs, as well as ‘dumbass’, and ‘ass’.

I don’t understand these priorities! But I do understand that this is an example of what is known as the Scunthorpe Problem.

The Scunthorpe Problem is a technological problem whereby content gets blocked or censored because a string of letters, an innocent string of letters, contains what would be, in other contexts, a rude word.

The reason this happens is at some point, some human has compiled a blocklist of words that, in their whole form, might be a problem: slurs, swears, that kind of thing. But of course language isn’t that simple, or at least the English language isn’t, you can’t spell ‘Scunthorpe’ without ‘Shorpe’, and programmers can’t program for every possible context every word might appear in. And the programs themselves don’t know what words are rude and what’s not, and moreover they don’t care, they’re not sentient.

The Scunthorpe Problem occurs a lot. For example, in 2020 alone, Twitter blocked hashtags about the British political troll Dominic Cummings, and Facebook kept banning users for posting about spending time at the seafront park in the southern England town of Plymouth that is called the Hoe. Hoe just means ‘high ridge’! Leave Plymouth Hoe alone! And that same year, the year of online conferencing, an online conference platform banned the word ‘bone’...from a paleontology conference.

If you have a surname like Cockburn or Hancock or Wang or Lipshitz then you probably know the Scunthorpe Problem. In South London, the Horniman Museum doesn’t receive all its emails. The Canadian magazine The Beaver, founded in 1920, changed its name in 2010 to Canada’s History so its mailouts didn’t get sent straight to spam. Even the term ‘specialist’ frequently gets blocked for containing ‘cialis’. Cialis isn’t even a swear! It’s a brand! And good luck bragging about graduating cum laude. Or trying to run a website about shitake mushrooms.

There’s also a subset of the Scunthorpe Problem, known as the Clbuttic Problem, where the word gets replaced by a more euphemistic one, resulting in messes like the Buttociated Press, the game Buttbuttin’s Creed, or clbuttical music, or the US consbreastution. That’s the Clbuttic Problem. Get it?

British place names are an absolute banquet to the hungry obscenity filters; there are whole counties with names ending in -sex. The Scunthorpe Problem could have been named after other many towns similarly affected, like the South Yorkshire town of Penistone, and Clitheroe in Lancashire, or Lightwater in Surrey - and I looked at Lightwater for ages on the map and thought, “What’s wrong with Lightwater that would get it flagged for rudes?” but eventually twigged that it’s not the ligh or the er.

Wake up, Helen!

The Scunthorpe Problem is named in tribute to the third most populous conurbation in the county of Lincolnshire, the town of Scunthorpe. In case you haven’t already clocked why Scunthorpe was chosen as the town to represent this condition, it’s because of what I’ll euphemistically refer to as the cunt-word.

The Scunthorpe Problem was diagnosed in 1996, and made the front page of the Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph, Tuesday 9 April 1996, final edition of the day.

It said:

The ban on Scunthorpe and that four-letter word was discovered by retired steelworks mill controller Doug Blackie of Cole Street when he applied to join AOL UK.

Each time he typed in the address Scunthorpe on his application he was met with the stock reply: "Your account cannot be processed any further.

Doug Blackie said:

"So then I typed in my address as Frodingham and bingo the block was lifted."

AOL had only been going in the UK for three months at this time, maybe it hadn’t been faced with the profanisaurus of British placenames yet, and the company recommended people respell Scunthorpe as ‘Sconthorpe’ while they worked on fixing the problem. But this was merely the beginning of Scunthorpe’s online troubles: well into the 21st century, safesearch filters blocked the websites thisisscunthorpe.co.uk and scunthorpedistrictcatsprotection.co.uk, getting overprotective there.

Now, like Elle Woods, I have questions.

Why Scunthorpe? How did this happen? How did Scunthorpe get this name that makes it a punchline and a tech problem?

Scunthorpe is an old old place name: we know this because of the Domesday Book, which as a name sounds dramatic but the Domesday Book wasn’t actually apocalyptic, it was the record of a huge survey done in the year 1086, the king sent men out across most of England and Wales to record who held what land, and what the worth was of each piece of land and the work thereon, to make sure they paid taxes and land rents to the landowners and the king got his. Sometimes the taxes were paid in the form of what the land produced, like honey, oats, salmon, pigs, beer and eels.

Whatever happened to eel-based economics, eh? Too slippery? At the time of the Domesday book, people using eels to pay taxes and land rents were collectively paying, per year, more than 500,000 eels.

WHAT ARE THE LANDLORDS DOING WITH ALL THOSE EELS? We must be told!! And this went on for another 500 years! Maybe that was the point at which the king realised that eel money is inconvenient. It keeps slithering out of my wallet.” Idea for keeping rents down: paying in eels. “Are you raising my rent this year?” Landlord: “NO! Pay me less rent, less rent! I’m drowning here!”

Anyway, the Domesday Book is this incredible record of 268,984 households all the way back in 1086 and a lot of place names that had originated from these people’s names are still in use today. One such place name being Scunthorpe. In the Domesday Book it was written as Escumetorp. The ‘e’ at the beginning was what is known in linguistics as a ‘prosthetic E’, didn’t change the meaning, just made a consonant cluster easier for people to say if the word was a foreign import to them and they were used to a bit more vowel, as the Normans would have been then.

The middle part of Escumetorp is Skuma, which was the name of the man who was the head of the household operating on that patch of land. ‘Torp’ or ‘thorpe’ was an Old Norse word meaning hamlet or homestead or estate, so Escumetorp meant ‘Skuma’s estate’, the Domesday book was documenting that Skuma owned that land.

So the part of the word ‘Scunthorpe’ that caused all these problems 900 years later is Skuma’s name. And if Skuma was around now, I would love to ask him: “What do you make of all this?”

[Martin Austwick sings:]

I was just some guy, not an important man.

My name’s in the book ‘cause I owned a piece of land.

There’s a town there now, and the town is wreathed in shame,

But it did nothing wrong

Except it bears my name.

It’s not my fault,

Who could predict this?

Nine hundred years,

And I start causing glitches.

It’s not my fault,

I didn’t plan it.

It’s just a name,

Like James or Jeff or Janet.

It’s just a name

Like James or Jeff or Janet.

HZ: In my non-scientific opinion, in British English, ‘ass’ is not a rude word. And we’d more likely say ‘arse’ anyway, spelled A R S E, and arse probably wouldn’t be asterisked or bleeped out - the words Arsenal and arsenic tend to survive intact. The word has a long history out in the open. In Old English, the medlar fruit was called openærs, as in ‘open arse’, because of what it looked like. Bowel movements were known as ‘arse-goings’. Medieval toilet paper was called ‘arse-wisp’.

Meanwhile, historically ‘ass’, A S S, had since ancient times referred to a donkey. In 15th century English, a donkey driver was called an ‘ass man’, how things change, there’s a little piece of information to file away for whenever you need evidence to contradict someone who insists language is set in stone. In the 16th century, ass gave us the word ‘easel’, because an ass bears loads.

‘Arse’ and ‘ass’ don’t share etymology, they’re both from unrelated ancient words that respectively meant bum and donkey, but the similar pronunciation brought them together in people’s brains, like how I now have to remind myself which one is right, home in or hone in. (It’s ‘home’.)

And 250ish years ago, polite speakers started calling the animal ‘donkey’ instead of ‘ass’, to be safe. A female donkey had been a she-ass, now rebranded as a jenny or jennet.

If you want an idea of changing mores around this sort of language, there’s a play from 1684, by the Earl of Rochester, called Sodom. You can probably tell from that title that it is an intentionally provocative and saucy play, and it was probably a satire on King Charles II’s religious policies.

But in it, there are dozens of uncensored instances of the word ‘cunt’, and there are characters named Fuckadilla, Clytoris (with a Y), Bolloxinion, Cuntioratia, and Cunticula. Whereas the word they did blank out was ‘Almighty’. Because what is offensive changes a lot over time.

Anyway, like Elle Woods, sharpest mind in the Delta Nu sorority, I have questions. Why Scunthorpe? Because none of this is related to Scunthorpe, there’s no reason for Scunthorpe to contain the cunt-word at all.

In the Domesday book, Skuma’s homestead was written as Escumetorp, and in the centuries thereafter while spellings were unfixed, there were several variations such as Scumpthorpe, with a P, Scumthorpe, Sconthorpe with an O, Scomthorpe with an O M, and Skunthorpe with a K.

Lots of better options! Although the scum ones would bring their own problems - however, plenty of choices that would be no trouble.

Spam filters would have no quarrel with Scunthorpe if someone had just taken the AOL executive’s suggestion a few hundred years earlier to go with another spelling - Sconthorpe with an O, or if they really wanted the Scunthorpe sound without the inconvenience, spell it with a K.

Which would be fitting, because Skuma was spelled with a K. Skuma didn’t have a rude word for a name.

[Martin Austwick sings":]

It wasn’t rude

Way back in history.

Nobody had

To asterisk me

It wasn’t rude,

No funny business.

It’s just a name

Like Fanny, Rod or Dick is.

It’s just a name

Like Fanny, Rod or Dick is.

HZ: Now, like Elle Woods, most astute law student interning on a murder trial, I have questions. Why Scunthorpe?

The town we now know as Scunthorpe grew out of five villages: Ashby, Brumby, Crosby, Frodingham and Scunthorpe. all of which were in the Domesday book, Brumby was the land of a man called Bruni. Frodingham was another guy, Frod. There’s also the neighbourhood of Yaddlethorpe, named after Eadwulf, a name that deserves to make a comeback.

For a long time, Scunthorpe was just part of the district of Frodingham, and all these villages were pretty small, until iron ore was discovered in the area in 1859, whereupon the population swelled with people coming to work in the mines, and the villages became a town. Scunthorpe had become the biggest village, so that name got applied to the whole town.

[Martin Austwick sings:]

The town could have taken someone else’s name.

Like my neighbour Frod,

Or Bruní down the lane

Eadwulf - he was a lovely dude,

Use his name instead, then it’s not remotely rude.

I didn’t think that I’d go down in history,

My children died, grandchildren died, who’s there to miss me?

You can’t control how things will go

when your life’s ended.

I didn’t know

This is how I’d be remembered.

You never know

Just how you’ll be remembered.

You never know

How you’ll be remembered.

HZ: All this was inspired by that Legally Blonde watchalong with the Allusioverse community, so if you fancy some of that serendipity like communally being wowed by examples of the Scunthorpe Problem - which I think have been fixed now when I went back to check - then join by donating as little as $2 a month via theallusionist.org/donate. In return you also get the company of your Allusionauts, regular livestreams where I read relaxingly from my collection of unusual dictionaries, inside scoops about the making of every episode, last month a bonus livestream with my other podcast Answer Me This, and most rewarding of all, you’re funding the making of this show, which makes you A Patron of the Arts and a Generous Benefactor, whichever you prefer. Pretty cool! To become such, go to theallusionist.org/donate.

Coming up on the show, it’s words with a different number of letters season.

The subject matter of this episode does not feel super appropriate to chase with an in memoriam, but this week, a friend died, Jonathan Main. I’d known him for close to twenty years - in Crystal Palace, the London neighbourhood I lived in for a long time, he ran The Bookseller Crow, a great independent local bookshop that to me really epitomised a great local bookshop, the kind of place you’d go in without a plan and come out with a stack of books and probably some cards painted by local artists too. And the soundtrack was always excellent. I had to buy extra bookcases thanks to Jonathan’s recommendations. You can hear him on the show too, way back in the earlyish episode called Big Lit. And as well as being a keystone of the community - and invaluable source of local knowledge and gossip - Jonathan was the link between comedians, musicians, poets, novelists, memoirists, writers of all genres, and readers of course. From behind the counter in a small shop in one suburb, his influence radiated far and wide and reached thousands of people. I hope he knew just how much he mattered.

Bookseller Crow managed to survive evil landlords, COVID, awful times in local retail, scores of people browsing and then ordering what they found on the big online river-named store - “But buying from the big online river-named store is so convenient!” yeah you could stand to inconvenience yourself more, for the common good. And now Bookseller Crow has to figure out how to survive the loss of Jonathan. His copilots, his wife Justine Crow and the writer Karen McLeod, are selling books, and vouchers for books, in person or at booksellercrow.co.uk, if you want to help them out during this difficult time. And if you’re lucky enough to still have a local independent bookshop where you live, and you’re able to go to places, go in and shop there, order books from there, buy the socks and the mugs and the pencils, attend events there. There’s something about independent bookshops specifically, the communities that can grow in and around them, that is very precious and does not get recreated if or when they’re replaced by a vape shop or an estate agent with promotionally-branded minifridge, or by the big online river-named store with its malign intent.

Goodbye Jonathan, I’m one of the many many people who will miss you terribly, and I have several hundred books to remember you by, so thanks for those. And everything else.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

hachures, plural noun: parallel lines used in hill shading on maps, their closeness indicating steepness of gradient.

Try using ‘hachures’ in an email today.

This episode was produced by me, Helen Zaltzman, on the unceded ancestral and traditional territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. The music and singing is by the singer and composer Martin Austwick; you can find his own songs at palebirdmusic.com.

Our ad partner is Multitude. To sponsor this show, so I can talk winningly and admiringly about your product or thing, get in touch with them at multitude.productions/ads.

And you can hear or read every episode, including all the other ones in Four Letter Word Season, get more information about the episode topics, and see the full dictionary entries for the randomly selected words, and find information about upcoming events such as next month’s book tour stop with that dreamboat Samin Nosrat, all at the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.

Allusionist 215. Two-Letter Words transcript

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, cheat on my own four-letter word season thanks to this suggestion from listener Erica: “Perhaps an idea for a bonus ep of a four-letter word season would be one on two-letter words: there’s an established list that Scrabble nerds end up memorizing, and it’s full of weirdness. For example: aa, oe, and mm are all acceptable words. But ew is not.”

Spoiler, ‘ew’ is now! It was added to the Scrabble dictionary in 2018. So, enjoy that.

Read moreAllusionist 214. Four Letter Words: Bane Bain Bath transcript

HZ: Wolfsbane, fleabane, bugbane, dogbane, leopard’s bane. All these plants are poisonous.

MARTIN AUSTWICK: Are these poisonous to those specific creatures?

HZ: It would be amazing to discover that a plant is poisonous only to leopards.

MARTIN AUSTWICK: “I fed it to my dog fine. Pet leopard, no.”

HZ: "I just need something to keep all these leopards out my flowerbeds, but I want the squirrels to be okay."

Allusionist 213. Four Letter Words: Dino transcript

lot of dinosaur names as well are just being factual about size, like ‘mega’ - and actually a lot of the names are being factual about other things, like triceratops and pentaceratops: that's descriptive. Three horns; five horns.

HANNAH McGREGOR: Five horns. We're always telling you about the number of horns. And then a lot of them are just like, “We found this in this place.”

HZ: Yeah. The albertosaurus -

HANNAH McGREGOR: Albertosaurus!

HZ: - in Alberta. And, mastodon is meant nipple tooth, or nipple teeth.

HANNAH McGREGOR: …Sorry?

HZ: You look a little perturbed,

HANNAH McGREGOR: Perturbed and delighted. Vagina dentata is a sort of recurring theme -

HZ: It's a passion of yours.

HANNAH McGREGOR: It’s a passion of mine! Ha ha ha. Yeah, yeah, you know what? You're not wrong. It's a recurring theme in the book and my life. and so I'm really, I am intrigued by the idea of adding nipple teeth into the equation.

Read moreAllusionist 210. Four Letter Words: 4x4x4 Quiz transcript

Four Letter Word season continues, and this time we do not require explicit tags or content warnings, because our four-letter word is QUIZ! Or rather, today we have a quiz about four letter words.

Read moreAllusionist 209. Four Letter Words: Serving C-bomb transcript

Things have changed for a word that despite being around in written text for 900+ years, didn’t even get listed in the Oxford English Dictionary until 1972.

NICOLE HOLLIDAY: I never say this word.

HZ: No, I feel bad to force you.

NICOLE HOLLIDAY: No, it's funny. Well, I'll say it on podcast, this is professional environment; but in my normal daily life, I can't imagine that I would personally say it. And this might just be like, I'm kind of a prude and I was raised kind of religious, but it does sort of seem like beyond the pale for me personally. I wonder if were 20 if I wouldn’t feel that way, but I spent so much of my life like judiciously avoiding very strong taboos. And this one, just my gut reaction is that it overwhelms. So when you asked me to do this, I was like, “Oh, no! I have to say that word!”

HZ: I'm sorry. We could probably skirt around it and then people can spend the whole episode trying to guess which word we're talking about.

Read moreAllusionist 208. Four Letter Words: Four Letter Words: Ffff

If you’re thinking, “How the fuck can you write a whole 500-page dictionary just about the word ‘fuck’?” consider, say, the many meanings of ‘ass fuck’, noun and verb - and that’s before you even add similar terms like ‘bumfuck’ and ‘buttfuck’. And there are so many less usual terms, like ‘fucksome’ or ‘fuckstrated’ or ‘fuckist’ or ‘fucktious’.

Read moreAllusionist 207. Randomly Selected Words from the Dictionary

Today’s episode is in the Tranquillusionist style, to give your brain a break while I say words that are not too consequential over a soothing backing track. And this time, the words are all the randomly selected words from the dictionary from every episode of the show, in reverse chronological order.

Read moreTranquillusionist: Ex-Constellations transcript

Let’s hear it for some of the constellations that we used to have but are now ex-constellations.

Read moreAllusionist 198. Queer Arab Glossary

HZ: So how do you go about building a glossary when you have to do that yourself from scratch?

MARWAN KAABOUR: Yes, it's a good question. Like, why would a graphic designer with a steady job decide to open this can of worms?

Allusionist 197. Word Play part 7: Word Sport

Unleash the bees!

Read moreAllusionist 196. Word Play part 6: Beeing

DEV SHAH: Spelling is about roots, language. I genuinely loved getting a word I didn't know and having all this information - it was like a detective case: you have the language of origin, the definition, alternate pronunciations, roots; it's like witnesses and having details to a crime scene, forensics. And, you know, it was just me piecing out together, doing what I love, in front of millions of people, shining on a stage, cameras, and still getting a lot from it.

HZ: And you got to do all that detective work in ninety seconds.

DEV SHAH: Exactly.

Allusionist 183 Timucua transcript

Listen to this episode and find more information about the topics therein at theallusionist.org/timucua

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, remove a tissue from language’s pocket before putting it in the washing machine.

This episode is about a project to reconstruct the lost language of extinguished peoples, and the surprises you can find about the people who had written it down.

Content note: in the episode there is mention of slavery, genocide, and mistreatment of indigenous people of what is now called United States of America. Also, if you have trouble hearing anything in this episode - or any of the other ones - remember there are transcripts of every episode at theallusionist.org/transcripts. And if you hear snoring during this episode, it’s not me, it’s an interviewee’s dog, it is not me.

On with the show.

HZ: Timucua is somewhat under-reported in scholarship of indigenous languages and literacy.

AARON BROADWELL: Yeah, I think that's really true. I think it was virtually undescribed until pretty recently. So these documents have existed for a long time, but because there are no longer Timucua speakers, I think that many of the details of how the language worked were very obscure until pretty recently. There's still a lot of open questions. We still don't know what other group of languages it might be related to. It's what linguists call an isolate, just meaning we don't know, but an isolate is sort of like an orphan linguistically; we know that it does have some kind of parents or some family it belongs to, we're just unable to say what that might be at this point based on the evidence that we have. Because it's not related to any other language that we know, because there were not any native speakers, because there's not a dictionary from the colonial period: all of those things were big obstacles in making much sense of Timucua language structure or grammar until pretty recently.

My name's Aaron Broadwell. I'm a professor of linguistics and also a professor of anthropology at the University of Florida.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: And I'm Alejandra Dubcovsky and I'm a professor of history at the University of California, Riverside.

HZ: What are you working on together?

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: What are we working on? We're working on translations of this amazing 17th century Timucua language materials, a language that was once spoken in what is now northern Florida.

HZ: The Timucua encompassed around 35 different tribes of Indigenous people living across a large area of what is now known as Florida and Georgia. Although these were separate tribes, they had some shared culture and politics, and they spoke dialects of the Timucua language.

AARON BROADWELL: And when the Europeans first came, there were a very large number of Timucua people. It's hard to estimate how many there might have been. Some estimates are in the range of a hundred thousand of them, but very unfortunately, these people were the victims of a lot of very bad things historically.

HZ: When the Spanish arrived in Florida, there were an estimated 100,000-200,000 Timucua people; just two centuries later, the Timucua population was down to one hundred.

AARON BROADWELL: They were allied with the Spanish, and the Spanish were losing control of Florida at that time, so there was a lot of warfare right on the border between the English and Spanish colonies. There was also disease and there was also slave-taking. So this population was greatly, greatly reduced. And when the Spanish left Florida and gave up St. Augustine to the English, they left to go to Havana, Cuba.

HZ: That was in 1763. And they took some Christian Timucua people with them.

AARON BROADWELL: So some of the Timucua ended up in Cuba. Others probably intermarried with other native groups of the southeast, although that's pretty unclear, but that's probably what happened. Other Timucua people were probably sold into slavery and maybe their descendants live among descendants of African-Americans in the southeast somewhere.

There are not a lot of people who identify as Timucua descendants, but that's probably because not a lot has been said about Timucua people until pretty recently. So we have had some contacts with a few people who have a family history that says that they are descended from these people. We think they will probably find more people over time. But that's kind of where they were. And so the dates that we know about them are from the first European contact in the 1560s or so up until about 1780s, which is about the time that the Spanish lose control. And we don't know when the last speakers lived. Probably maybe the early 19th century might have been the last time that someone spoke the language.

HZ: But the Timucua language was partially preserved in texts. Going back a few years down the Allusionist back catalogue, we talked in the Key episodes about some of the translation and reconstruction methods used with languages which have no remaining speakers and not much in the way of explanatory materials. Here’s how Aaron made progress in understanding Timucua.

AARON BROADWELL: Getting to read the language, the Timucua original was a really hard problem. Maybe I first glanced at these materials, you know, maybe more than 20, 25 years ago, and kind of decided the problem was too hard, that it was just impossible to read the original without a good grammar or dictionary of it. But linguistic software has gotten a lot better, and there's some free powerful linguistic software that a lot of linguists use that allowed me to put in a lot of the text and then use the computer to help me search for certain kinds of patterns and the data. And it was through that kind of computational method that I started to crack certain parts of the grammar of the language.

And once I kind of understood the grammar and I had hypotheses about the meanings of the words, I could start to put together what the original Timucua says. So there was kind of a long journey of grammatical discovery with me and Timucua slowly working out what it all means. And I think I understand the great majority of Timucua grammar at this point, but there are still, you know, difficult passages in there. There are some unexplained little thickets, basically, where the Spanish is not parallel and the Timucua is saying something complicated that I still cannot read. But I have hoped that at some point I'll be able to read all of it. Just at this point, I can read most of it, especially the clear parts, and I can sort of understand what they are saying.

HZ: Aaron and Alejandra have around 138,000 words written in Timucua language to work from, and most of them are in the form of missionary texts. A writing system for Timucua was developed using the Latin alphabet by the Franciscan missionary Francisco Pareja, who taught Timucua people to read and write, then published several books in Spanish and Timucua: catechisms and other religious tracts, and a Timucua grammar.

AARON BROADWELL: And these texts are the oldest text in a Native American language from the US. They're written many, many decades before anything earlier from the US. So the earliest are from 1612.

HZ: How come Florida is thus honoured?

AARON BROADWELL: Florida is one of the first places where the Spanish established a colony. So in 1565, they established the city of St. Augustine, Florida. And then in the decades that followed, these Franciscan missionaries came from Spain to try to convert the local people to Christianity.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: And they're only going to towns in which received an explicit welcome. I think this really important. It's not like they're setting shop and people are coming to them. It's the other way around. And in fact, it takes an uprising in 1656 for that really for that change and for the missions to really much more follow a Spanish model. And these spaces are really indigenously driven and dominated.

HZ: There were surprisingly few Franciscan friars out there in Florida trying to convert the locals - only about seventy, at peak Franciscan friar.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: And these Franciscans depend on native people to feed them, to bring them grain, to provide for them, to bring them water, all those things. And these are spaces in which the Spanish, they very much understand that they need to work with the language if they're gonna have any success, because Spanish is not the dominant language that's being spoken at moment of time.

AARON BROADWELL: And so part of their process of conversion involved establishing some schools where the kids learned to read and write their native language. They didn't have a written form of the language before the Spanish, but the Spanish missionaries worked out a way of writing it using the Roman alphabet. And they taught it to the kids in these schools, and then they translated Catholic religious material into the language and taught the kids to read the catechism, the confessional, that kind of thing.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: These are also used for the Franciscans themselves, so they can learn to properly take and grant communion and all the sacraments, confession and the like, so that could be also done not just in Spanish or Latin, but in the Timucua language, so they could be, in theory, better ministers of the faith by communicating with indigenous people in their own language. So these are texts that are supposed to be indoctrinating for other people, but also tools for themselves to guide.

HZ: As we heard from Caetano Galindo earlier this year in the episode about Brazilian Portuguese, it was often easier for European Christian missionaries to learn the languages of the people they wanted to convert, rather than make them learn a whole new language then convert them to Christianity.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: But you also see a lot native people it upon themselves to learn Spanish, so you see some Timucuas who are learning Spanish in the documents who were serving as translators and were playing a pivotal role in this process.

HZ: The Spanish colonizers and the Timucua, were they using each other's languages to an equal degree?

AARON BROADWELL: To some degree we don't know. But in most colonial situations that we're able to observe in the world, what we see is that most of the burden of bilingualism falls on the native people. So they are kind of obliged to learn the language of the colonial and not so much the other. We know that the Franciscans, to some degree, could speak Timucua and could communicate and maybe lead prayers and things like that.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: And in this early 1600, we're in this moment where there's a big push to learn and work with indigenous languages. And Francisco de Pareja, who is the main Franciscan who works on Timucua - he's not the only, but he's one of the main - he spent a long time sort of praising himself about how important it is to work on this language, and how dadada. And he gets on his high force and then provides a bunch of examples and basically prove he doesn't have as much control of the language as he thinks he does.

AARON BROADWELL: I think maybe the civil authorities, like the soldiers, the state power in St. Augustine, probably could not read Timucua. So I think that the Spanish often relied on native interpreters to do their work. Probably, I would say, the people most likely to have been bilingual would've been native people and Spanish religious officials.

HZ: What do these texts look like? There are some where you've got both the languages side by side, right?

AARON BROADWELL: Right. One model is the two languages and two columns like Spanish on the left and Timucua on the right. Those are usually the simplest texts, where the Spanish is just maybe like one sentence. But then we also get these really complicated things where there'll be like three or four pages of Spanish and then four or five pages of Timucua after that. So one of the problems for the linguist is you have to figure out how to match those two things with each other, which is extremely tedious. And another thing that happens is the Spanish is only like four or five lines, and then there are four or five pages of Timucua after that. So the Spanish is just a little summary, it’ll say something like, you know, “God created the world in seven days, blah, blah, blah, et cetera.” And then it goes in Timucua, which goes on and on and on with lots of details about this. Those are some of the most interesting parts of the Timucua literature. They don't have any Spanish translation, so we're reading those for the first time, and we can read some parts of that and not others. But a cool example is that the text describes the creation of different things that live in the air and on the land and in the water. So there's a long list of things that live in the water. We know the words in there for whale and certain names of fish, and we can guess at what some of the others of them mean. But it's kind of a nice list of living things.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: And the Spanish has none of that. So the Timucua gives you a sense of people, especially coastal Timucuas who are doing some farming, but the majority of their food is coming from waterways, it's coming from gathering. And so, just a really different way of understanding the world, right? The Spanish are saying, “The world was created in seven days, there we go.” And Timucua writers sit down and think about their own world and document it.

HZ: Usually, religious documents like these don’t give you that much insight into the people writing or translating them, because there’s not colloquial language or scenes from everyday life in there.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: And they're so boring! And they're not joyful to read; they're repetitive, they're doctrinal, they're heavy. So they were not exciting texts necessarily work with, except perhaps like these momentary sections within the text that seemed to describe something particular about Timucua culture and life.

HZ: The Timucua text is not a direct translation of the Spanish - often far from it.

AARON BROADWELL: So one of the things that we started to notice really early on in looking at these documents is that the Timucua does not say the same thing as the Spanish. So the texts almost are never exactly the same. The Timucua almost always clarifies or explains in some way, adds something or omits something. And we started to get interested in the patterns of what's added or omitted from the Timucua, and so a very general pattern that we found is that pretty often the Spanish text says something fairly negative about traditional Timucua practice. For example, we've got a text that says something like, "Did you engage in the devilish practice of whistling at the wind in order to make the storm stop?" And then when we can properly read the Timucua, it just says something like, “Did you whistle at the wind to make the storm stop?” So the Timucua writer is doing this editing function of taking out certain parts of the Spanish. So early on we see the Timucua writer has their own voice. They take things out when they disagree with them, or they add things in as well when they think that the Timucua readers need more context or more explanation.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: This is not just a moment of Spanish bad translation, right? There's active agencies in these discrepancies between the Spanish texts and the Timucua text, the removal of these condemning that's like violent and, and, definitely harmful language that's just absent in the Timucua text, in these key moments where the Spanish is very, very damning. And all of a sudden we're like, this is huge! The moments of mistranslation where you see not just like a misunderstanding, but a different text that emerges.

HZ: For instance, in the Timucua rendering of the story of Adam and Eve.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: We all know the Spanish, blaming Eve for her choices, her ability to be so persuaded by the snake. And this is not the first time, but we've seen moments where women in the Timucua version get sort of more limelight than in the Spanish. The Spanish often has them as part of the sentences, but they're often not tied to any verbs, they're just there. But in the Timucua, they have action to them: they're doing things, they’re making choices. Often they speak in the Timucua and they don't speak in the Spanish.

And Timucua Eve is just - I mean, she's just a badass! She says she wants to eat this apple, whether the snake wants it or not. In the Timucua it's almost like you're hearing her thoughts, she's thinking, and she sort of says like, “If I take this to my husband and he eats this, he's gonna be the boss of me, and I don't want him to be the boss of me, I want to be the boss.” And so she eats the apple. And the word she uses for boss is ‘parucusi’, a Timucua word for war chief. So not just any chief, but a very particular military position of power, which is traditionally men - I have not found women in that role. So here in this incredible translation of it, the woman is just not only far more active, but has a lot more sort of choice and agency in her story.

And again, the negative is almost gone from that. It's like, you are supposed to understand that that's a bad thing, that she wants to be the boss of her husband. But in the Timucua it’s not necessarily - maybe the parucusi element of it is hinting at a transgression that she's making, but it doesn't have that component. And that is just extraordinary. That was one of my favourites.

HZ: The Timucua version is also more frank about sex than the Spanish. Where the Spanish text says, “Speaking with some woman or embracing her or taking her hand, did some alteration come to you?” the Timucua version does not go for a euphemism like “alteration”. It says, “Did you get excited and did the flesh of your body stand?” (Boners, it means boners.)

AARON BROADWELL: I was also going to mention that if you just read the Spanish text, it has a very European stereotypical view of gender and marriage. But we know from other kind of evidence that the Timucua had a third gender role and that marriage practice was substantially different than it was for the Spanish Catholics. And so when you look at the questions in Timucua that deal with marriage, one of the things you notice is there's just a general word that means spouse. There's not different words that meet husband and wife. and there are no genders in the pronouns either. The Spanish might say something like, “Did you forgive your wife when she walked with another man?”

HZ: “Walked.”

AARON BROADWELL: “Walked.” Right. And the Timucua will say something like, “Did you forgive your partner when they wanted to have sex with another person?” So no genders there in the Timucua. And so what we see is that if you're able to read the native text, what you get is a far less stereotypical gender situation. You get a Timucua text that's much more flexible in terms of the genders or identities of the people involved.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: Absolutely. And it insists on it. So as the Spanish text very clearly sort of asks questions that are gendered, that very clearly says like “your wife, your husband, your man, your woman” - and there are words in Timucua for man and woman - the Timucua is not using not those words. We'll get caught in this ourselves: we'll be translating and all of a sudden we're like, “Did the text actually say ‘man’?” And we go back and go, the text never said ‘man’. And we have to go back and take out our own gendering as we translate.

HZ: Something else that caught Aaron and Alejandra’s eyes was a section of text where the Spanish question Timucua food practices.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: This is this particular section which is asking about what the Spanish call superstitions or ceremonies or practices - and again, using clearly charged negative Spanish language. So these are not like, “What were the customs you did?” There's a sort of damning element, even to the structure, the way the Spanish are asking. And there are questions about food in there and the ways in which Timucua people consume food, preserve food, pray over food. “How do you fish? And do you pray in any particular ways after catching the first fish, or even after creating your first trap? Do you pray over that?” And the Spanish are saying all those things are bad and sinful, “You shouldn't pray over your fish, you shouldn't pray over your new catch; you should just pray to the virgin. You should pray to the correct Catholic order. You shouldn't be praying, that's heathen, that's pagan.”

You see questions; the Spanish are curious in efforts, often to clamp practices down, but they are asking about all that. And you have to understand that for a lot of the Franciscans, they are totally dependent on native people feeding them. So they are paying attention to this world, in part because they need to to survive in this world. They're not in a comfortable space where the majority of people look and talk like them. They’ve got to be on people's decent graces if they're gonna eat the next meal and survive the next day.

HZ: Yeah, it does seem like a bold move to neg the local culture if you don't wanna die.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: They do that too. There are two surviving letters written by Timucua people. These letters, the 1651 letter and the 1688 letter, begin to give us some sense of this sort of the tremendous violence that's occurring in these places. And I think this is very important, because there's way in which mission history can very sanitised. And I'm rooted here in California, and there's a huge wave of rethinking the missions in California and thinking about incredible violence, and the word ‘genocide’ is much on the forefront of Californian missions study. That is not at all where Florida missions and historiography is at all. Even documenting that the fact that these spaces are not just learning environments, but fact very oppressive. The Franciscans are recording practices they want to clamp down on, and you see in other documents from the officials that are recording the sort of drastic population decline as a result of the disease, as result of abusive labour practices, as a result of people migrating out, because they don't want to be part of this.

AARON BROADWELL: You might also ask a question like who were the Timucua writers that we're talking about? Mostly we don't know their names because the Spanish never gave credit to native people for writing and translating things. But certain particular styles, word choices or spellings allow us to allow to identify different authors in the text. So you like author A, author, B author, C. Some of your listeners might be familiar with, for example, the Hebrew Bible: we know that there probably are different writers in there too, there’s the J author and the E author and so on. You can tell by different word choices they make in the Hebrew text. In the same way, we can identify different authors in the Timucua text.

HZ: They do have a small handful of names of Timucua writers - the people who signed those two letters that were written in 1651 and 1688.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: Even their names themselves tell you this deeply colonial story, because they were all signed with a Spanish name, often with the honorific marking Don, so they'll be like Don Pedro, but then they'll say ‘olata’ [?] which is a Timucua marker for a chief or someone of ranking or authority. And they include their town name, often both the town name in Spanish - you know, San Pedro, San Pablo, whatever - and then the Timucua word next to it of that. So even in their signing in the 1688 letter - and if you think about it, 1688, we're talking a hundred plus years after colonization. So this is deep in the process of the colonising. We always say colonization is a process. It's not a one time event. Well, here we are, deep in that process - even in the names that writers assign themselves. You see this high effort of who they are as Timucua people writing in their own language and using all these honorific markings. That letter is amazing. As Aaron has alluded, they're very clear about who they respect and who they don't respect and that only comes out if you work on the Timucua language.

HZ: What ways were the Timucua people using writing as a sort of tool of resistance?

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: In one of the early conquistador stories, you’re thinking of first encounters, sort aliens coming meeting for the first time: native people do often things of like tricking the Spanish by putting up fake crosses and things that look like letters, to trick the Spanish. So even the earliest understanding of writing, as a tool or a technology that indigenous people can use themselves for their own purposes to undermine Spanish goals, is there from the get-go. And definitely by the early 1600s, when these become part of the way Franciscans are communicating, Timucua people really readily pick this up as a way for them, of course to learn the Catholic faith and communicate it, but also to interact with one another, exchange information across vast distances and the like.

But there's also all the literary resistance that we've been talking about, about expressing their own beliefs within these really religious texts, and instead of expressing condemnation to their own beliefs or downgrading them, preserving them, in fact sort of maintaining records of them and expressing them in ways that are beyond not being condemning, they're in fact preserving and enduring of the Timucua language and ideas and expressions. So I think that's a literary resistance that's there too.

AARON BROADWELL: Alejandra mentioned this 1656 rebellion, it's called the Timucua Rebellion. We know from the history that it was partially organized by chiefs sending written letters from one village to another. The letters have not survived, but we have historical accounts that mentioned these letters, Timucua language letters going back and forth between the chiefs to help organize the rebellion.

ALEJANDRA DUBCOVSKY: Also, using the written word to write petitions to the Crown, to write petitions to the governor: that's a very common practice throughout the Spanish Americas of petition-making. So the fact that Timucuas are engaged in this sort of intra-indigenous process of resistance gives us a sense that they're really plugged into how to not just understand the colonial world, but how to fight against it as well.

AARON BROADWELL: You can think of writing as a kind of technology that originally the colonials bring for their own purposes to kind of use to control native people. In that way, it's kind of like the horse or the gun. But these technologies very quickly get out of control, and native people appropriate them and use for their own purposes.

HZ: You heard from Aaron Broadwell and Alejandra Dubcovsky. You can find more of their work on Timucua at Hebuano.org, where you can learn Timucua grammar and vocabulary and look at some of the texts. Aaron’s book of Timucua grammar is due out in 2024, and Alejandra recently published the book Talking Back: Native Women and the Making of the Early South. I’ll link to all these things at theallusionist.org/timucua.

The Allusionist is an independent podcast and if you want to help keep it going then recommend it to someone, the best way, I think, to find more podcasts we might love is word of mouth - or word of typing fingers? Actually, figuring out synonyms for expressions that aren’t quite covering it is one of the things we do in the Allusioverse Discord community, membership of which is one of the perks if you become a donor at theallusionist.org/donate. You also get behind the scenes info about every episode, and fortnightly livestreams where I read from a different dictionary from my collection, and we have regular watchalongs: at the moment we’re watch the new season of Great British Bake Off, later this month there’s Death Becomes Her, and we learned from last month’s watchalong of Legally Blonde that the subtitles asterisked out ‘ass’ - including in words such as ‘***set’ and ‘***ociate’. Which only served to make some fairly drab terminology seem saucy! Join us for thrills like these and so many more: theallusionist.org/donate.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

nival, adjective: of or relating to regions of perpetual snow.

Try using ‘nival’ in an email today.

This episode was produced by me, Helen Zaltzman, on the unceded ancestral and traditional territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

Music and help was provided by Martin Austwick of palebirdmusic.com and the podcasts Neutrino Watch and Song By Song.

Our ad partner is Multitude. If you have a product or thing about which you’d like me to talk, sponsor the show: contact Multitude at multitude.productions/ads.

Seek out @allusionistshow on YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, Bluesky, the chalk outline of Twitter… And you can hear or read every episode, find links to more information about the topics and people therein, donate to the show, and see the full dictionary entries for the randomly selected words, all at the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.

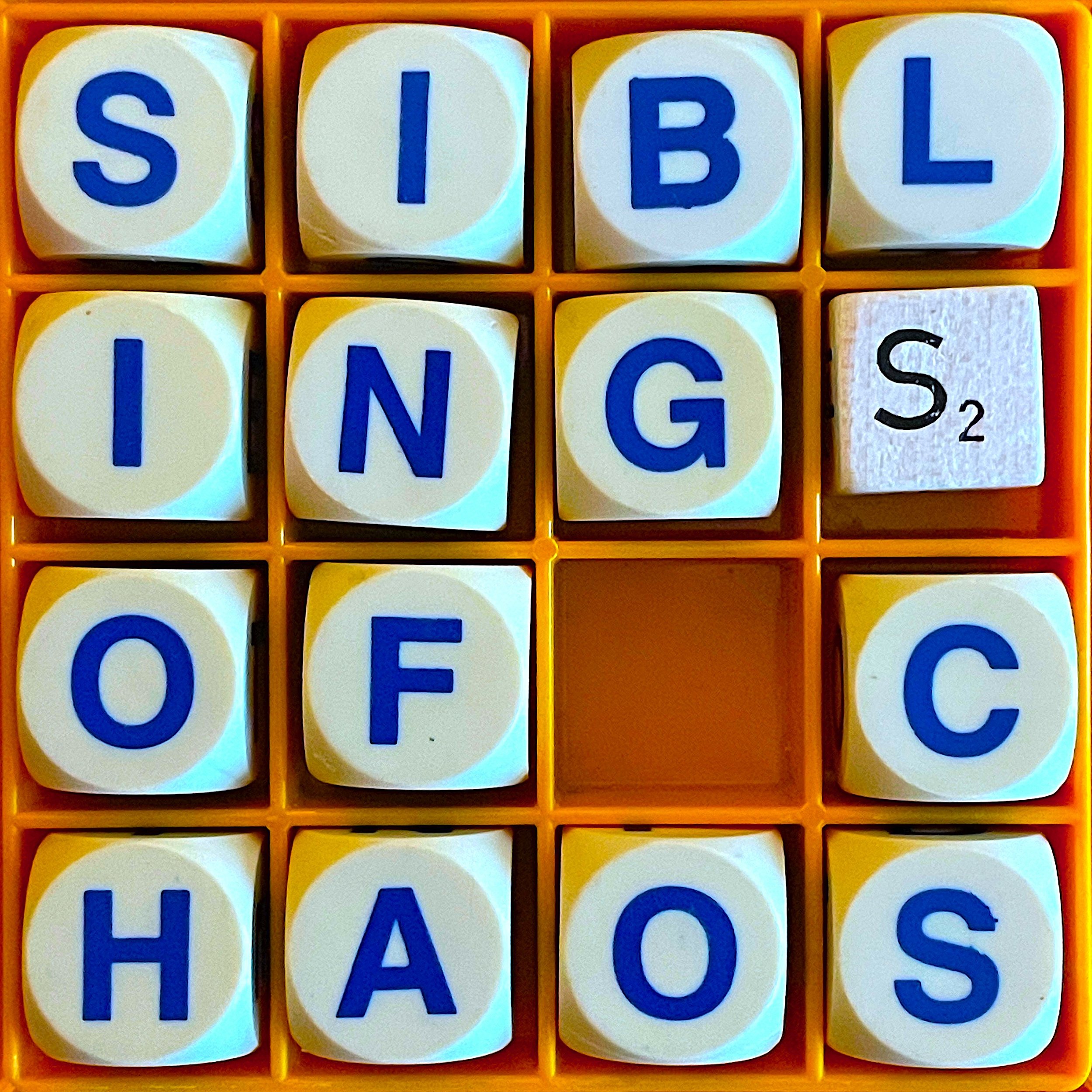

Allusionist 182 Siblings of Chaos transcript

HZ: I thought the etymology of 'gas' was a big surprise as well.

SUSIE DENT: Oh, yes. It is a sibling of chaos.

HZ: In a sense, we're all siblings of chaos.